The Origin of Species

What is this passage mostly about?

The cane toad is the Darth Vader of the amphibian world. A native of Central and South America, the lumpy toad was turned loose in Australia in the 1930s. Farmers hoped it would eat the beetles that were damaging sugarcane crops. The toad made itself at home, spreading steadily across the land.

As the toad multiplied, though, conservationists started to worry. The toad secretes a goo that can be toxic when eaten. Some feared that the imported amphibian would kill off snakes, crocodiles, and other local predators.

Minden Pictures/SuperStock

For years the cane toad has been the poster child of invasive species. An invasive species is a plant or an animal that settles in a new region, where it does harm to the environment, the economy, or human health.

Conservationists regularly take up arms against plant and animal invaders by trapping, hunting, poisoning, or bulldozing them.

A growing number of scientists have now begun to argue, however, that conservationists are too hung up on the native versus nonnative distinction. “The public has embraced the idea of hating nonnative species,” says Mark Davis, a biologist at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn. “There’s no scientific basis for that.”

Hitching A Ride

It’s easier than ever for people to move around the planet, often bringing other species along for the ride. Sometimes that’s done on purpose. Gardeners have been moving desirable plants from continent to continent for centuries. Other times, nonnative species are accidental tourists. Zebra mussels arrived in the Great Lakes after being inadvertently toted across the ocean in the ballasts of ships.

Scientists estimate that some 50,000 foreign species have settled in the U.S. Among them is the python, a 6-meter (20-foot) Asian constrictor. Florida pet owners dumped pythons into the wild and they’re now spreading across Everglades National Park. Another is kudzu, a vine from Japan that grows as much as a foot in one day and is running rampant across the southeastern U.S. Then there’s the zebra mussel, which clogs water pipes and has done hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to power plants and water utilities around the Great Lakes.

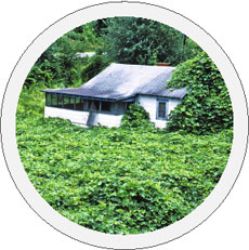

Jack Dermid/Photo Researchers, Inc.

Kudzu, an invasive Japanese vine, has spread across the United States. Here it is seen engulfing an old home in North Carolina.

Billions of dollars are spent in the U.S. alone to control

invasive species each year. Tim Male, vice president of conservation policy at Defenders of Wildlife, says the country should do even more to fight nonnative species. “It’s rarer than it should be that people are going out and trying to control nonnative species in some of our most special habitats,” he says.

Male and his colleagues are engaged in the preservation of the country’s ecological niches. An ecological niche is a unique position that a species fills in an ecosystem—the species’ habitat, the food it eats, and the predators that eat it. If nonnative species are allowed to invade local niches, Male says, “we’re affecting the species that are present now, and we’re also significantly affecting the future web of life, forever.”

Davis agrees that some nonnative species are harmful. And he agrees that vigorous efforts should be made to prevent the accidental introduction of foreign species to new habitats. But too many biologists assume nonnative means harmful, he says. He and 18 other ecologists made that case in the scientific journal Nature this past summer. “It is time for scientists, land managers, and policy makers to ditch this preoccupation” with nonnative species, they wrote.

Some nonnative species aren’t as bad as they’re made out to be, say the ecologists. Take the cane toad, the horror of which hasn’t lived up to the hype. While the toad’s presence led to a decline in some predator populations in Australia, most species weren’t impacted at all, scientists reported recently. Some species actually benefited from the toad’s arrival.

And consider the salt cedar, a shrub brought from Africa and Eurasia to the western U.S. in the 1800s. Between 2005 and 2009, the U.S. government spent $80 million fighting the shrub because it’s suspected of soaking up too much valuable groundwater from its desert habitat. But, notes Davis, the shrub is now the favorite nesting site for the southwestern willow flycatcher, an endangered bird. The shrub may be doing more good than harm.

Keith Douglas/All Canada Photos/Corbis

Honeybee

Some nonnative species do nothing but good. Honeybees are an example. They pollinate more than 100 crops in the U.S., providing an estimated value of more than $9 billion a year. Honeybees are an import from Europe, but nobody’s suggesting they buzz off.

Native species, on the other hand, aren’t always helpful. Mountain pine beetle outbreaks occur periodically in the forests of western North America. Millions of trees perish as the beetle larvae eat their way through the trees’ trunks. The mountain pine beetle is currently killing more North American trees than any other bug. It’s a homegrown hazard.

Claude Jardel/Biosphoto

Mountain Pine Beetle

Land Management

Instead of waging war on foreign species, Davis says, conservationists should figure out how to include them in land management plans. In general, he notes, the introduction of nonnative species results in more species in a given habitat, not fewer.

Claude Jardel/Biosphoto

Python

To Davis, the lesson is clear: “Don’t judge species on where they came from. Judge them on what they are doing.”